By Heraclitus Herac

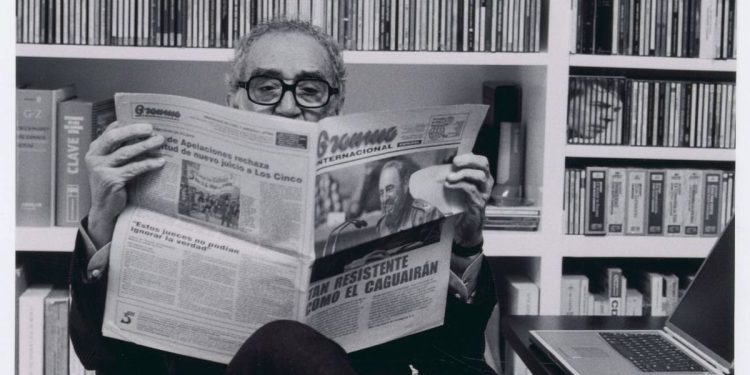

When I first read One Hundred Years of Solitude, I felt a profound need for a novel that would capture the essence of our own region—a novel titled Fourteen Hundred Years of Ignorance. Because here, ignorance, blind conformity, and intellectual bankruptcy are not the tragedy of a day, a year, or even a century; they are an unending catastrophe, passed down from generation to generation. I wondered: if such a novel were to be written, narrating our history and collective psyche in the same magical realism that García Márquez mastered, what would it look like?

This is the land where knowledge is considered a crime, questioning is deemed blasphemous, and inquiry is labeled as sedition. Here, people measure truth not by reason but by faith—faith that is spoon-fed by madrasa clerics, political preachers, or self-proclaimed scholars on social media. It is no surprise that we keep running in circles, each time arriving at the same old fatwas, the same threats, and the same insults that have echoed for centuries.

When the people of Ignorantistan first saw a mirror, they were bewildered. Some thought it was sorcery, some a conspiracy, and some declared it a satanic device and shattered it. The village elders gathered, stroked their beards, and issued a decree: “This is the eye of the devil, watching our deeds.” And thus, the first mirror in the history of Ignorantistan was deemed a sin. This was the same land where questioning was a crime, research was heresy, and thinking was rebellion. Every morning, the people of Ignorantistan would wake up, glance at the tattered calendar on the wall, and resolve to do exactly what their ancestors had done.

Imran was the strangest man in this village. One day, while sitting in the madrasa, he asked, “Maulvi Sahib, if the Earth is stationary, then why do scientists say it moves?” The grand cleric stroked his beard, spun his rosary faster, and declared, “This boy has gone astray. He must be brought back to the path of righteousness immediately.” And so, Imran was accused of the same ancient sins—heresy, blasphemy, and sedition. He knew that if he continued asking questions, he would meet the same fate as Socrates. So he learned to stay silent because, in Ignorantistan, those who questioned were either declared insane or simply made to disappear.

This was the same Ignorantistan where Mahmood of Ghazni was celebrated as a hero for launching seventeen invasions but never built a single library. Where Timur’s massacres were a source of pride, as he filled the Ganges with corpses but never lit a single lamp of knowledge. The Mughal emperors erected palaces, but their scientific contributions amounted to little more than a few experimental cannons. While in Europe, René Descartes declared, “I think, therefore I am,” in Ignorantistan, the decree was issued: “Whoever questions will be cast out of Islam.” The result? They reached the moon, while Ignorantistan still debates whether space travel is even permissible.

In the madrasas of this land, the Earth is taught to be stationary while the Sun moves. If a child dares to ask, “But Maulvi Sahib, NASA says otherwise?” his faith is declared at risk. In schools, instead of scientific inquiry, children are taught, “We will make rivers of milk and honey flow,” while in reality, they cannot even manage to keep their sewage systems functional.

Here, religion is not a personal journey but a social weapon, wielded by whoever holds it. The cleric uses it as a muzzle, the politician as a vote-harvesting machine, and the common man as an answer to every difficult question. Nietzsche once said, “Beliefs are truths we stop questioning.” And in Ignorantistan, those who question beliefs do not live long.

Not everyone here is ignorant, but every wise person is silent. Speak, and you will be labeled a blasphemer. Think, and you will be branded a rebel. Ask a question, and sooner or later, you will either flee the country or be quietly erased. Socrates once said, “A life without inquiry is not worth living.” But in Ignorantistan, an unquestioned life has become the very fabric of the system.

This is the same country where a YouTube cleric proclaims, “Muslims were the true inventors of airplanes,” and people applaud. But if a child asks, “Then why haven’t we built another?” he is told, “Your faith is weak!” Here, people sit at street corners cursing the West, yet their greatest desire is to obtain a visa to live there. The West is labeled a den of moral decay, yet the moment someone becomes wealthy, they dream of sending their children to Oxford. Voltaire put it best: “Hypocrisy is one of humanity’s greatest weaknesses.” In Ignorantistan, hypocrisy is found in abundance on every street corner.

Outside every mosque, a sign reads: “Lying is forbidden.” Yet inside, the cleric builds his house with the very donations he collects in the name of piety. Those who preach virtue lock their daughters away at home but never miss a chance to ogle another man’s sister or wife. They deliver passionate sermons on women’s modesty while dismissing street harassment as “just men’s nature.”

This is the same land where people long for a caliphate, yet the day traffic laws are enforced, they cry out, “This is a Zionist conspiracy!” If time in Macondo moved in endless loops, then in Ignorantistan, it has remained frozen in a never-ending cycle. The questions of a hundred years ago remain unresolved. The lies told a century ago are still being peddled. The same illusions are being sold, again and again.

And so, fourteen hundred years of ignorance have passed in Ignorantistan, yet no light is in sight. Because the people of Ignorantistan are in love with their own darkness—and perhaps they will remain so for another fourteen hundred years. By then, this world will have turned into a living hell.

Note: The “Qalam Club” does not necessarily agree with the personal views of the authors