By: Heraclitus Herac

Philosophy is often seen as a dry and serious subject, but if you sprinkle in some ancient Chinese wisdom, it becomes as engaging as a martial arts film—minus the Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee fight scenes, and with Confucius and Laozi wielding intellectual swords instead.

There was a time in China when every street corner, tea house, and gathering was buzzing with new ideas, much like today’s social media where everyone is a self-proclaimed philosopher. This era, known as the Hundred Schools of Thought, was not your typical school where students were scolded for not standing straight during morning assembly. Instead, it was an intellectual battleground of diverse philosophies and schools of thought.

While Greek philosophers were busy unraveling the mysteries of the universe and searching for the “ultimate reality,” Chinese sages were more concerned with practical matters—politics, ethics, and human behavior. Where Socrates and Plato pondered, “How was this world created?”, Laozi and Confucius were more focused on, “How does this world function?”

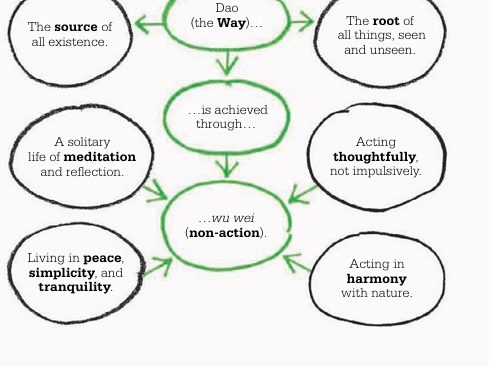

One of the most fascinating Chinese philosophers, Laozi (also spelled Lao-Tzu or Lao-Tse, take your pick), introduced a profound concept called Dao. But Dao isn’t just any idea; it’s the natural flow of life—like the course of rivers, the cycle of day and night, or Pakistan’s cricket team making it to the semi-finals only to break hearts. (Well, not even that happened this time!)

Between 1600 and 1045 BCE, the Shang dynasty firmly believed that fate was determined by divine forces. They worshiped their ancestors, hoping to win some cosmic favor—perhaps a thriving business if their forefathers were pleased or a locust plague if they weren’t.

Then came 1044 BCE, when the Zhou dynasty took over and “explained” to the people that ruling authority came by divine decree. Essentially, kings ruled by heaven’s mandate, meaning their legitimacy was divinely ordained. And when a king himself declares that his reign is “God’s will,” what choice does the public have but to accept it? Political decisions were conveniently labeled as “heaven’s will”—if the king raised taxes, it was fate; if people complained, they were rebels, bound for prison.

It was in the midst of this political and ideological wrestling match that Daoism emerged, gaining traction in the 6th century BCE. China, at the time, was embroiled in internal conflicts, civil wars, and power struggles. The Zhou rulers and the elites had mastered the art of governance, commerce, and court intrigue. Success in that era depended either on excelling in courtly manipulations or developing an alternative philosophy—something Daoists did brilliantly.

Laozi famously said, “To know others is intelligence, but to know oneself is true wisdom.” In modern terms, if you know the WiFi password, you’re smart; but if you know that life without a phone is possible, you’re truly wise.

Ancient Chinese thinkers believed that everything is in a constant state of transformation—day turns into night, summer into winter, prosperity into crisis. Nothing is permanent; rather, everything is interconnected and in a continuous state of flux.

Laozi stated that the world contains “ten thousand things” (meaning countless phenomena), and humans are just one among them—neither superior nor inferior to nature. In his view, we are all part of an organic order, without any special entitlement.

But where does the problem arise? The issue begins when human desires and stubbornness interfere with this natural flow. Nature intends for us to live balanced lives, yet we scroll endlessly till 3 AM and then curse fate when the alarm goes off in the morning.

According to Laozi, a good life is one where we align ourselves with nature—not forcefully, but effortlessly. This philosophy is best encapsulated in the Dao De Jing, a book that stunned the world. While tradition credits Laozi with its authorship, some scholars believe it’s a compilation of multiple sages’ teachings. After all, Laozi was so enigmatic that he might as well have been a mythical figure.

Legend has it that one day, Laozi decided to leave civilization and quietly cross the border. A clever guard recognized him and requested, “Master, before you leave, share your wisdom in writing!” Laozi nodded, picked up a brush, and swiftly penned the Dao De Jing, much like a blogger rushing to complete an article at the last minute.

So, if you want a better life, follow the Dao—flow with nature, don’t resist it. If your car is stuck at a red light, instead of honking impatiently, enjoy the moment. Because that’s what Daoism is all about—moving with the rhythm of nature rather than against it.

Note: The “Qalam Club” does not necessarily agree with the personal views of the authors